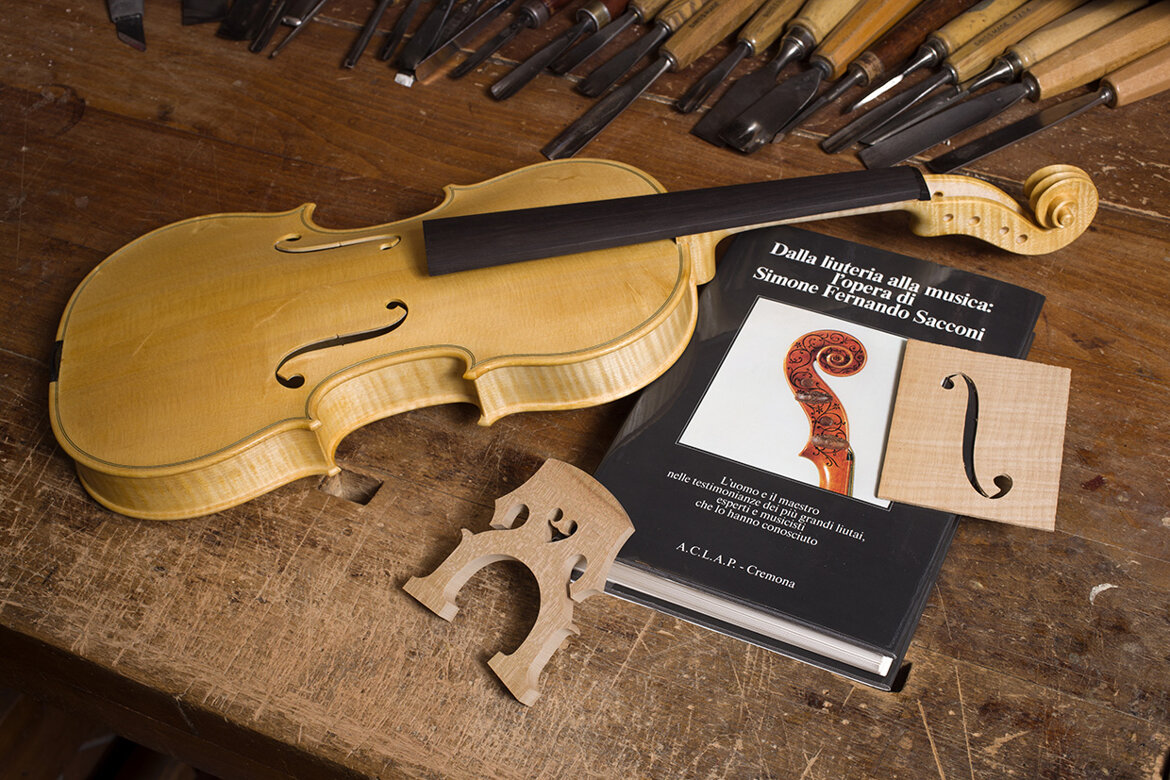

The book «Dalla liuteria alla musica: l'opera di Simone Fernando Sacconi / From Violinmaking to Music: The Life and Works of Simone Fernando Sacconi» conceived and promoted by luthiers Francesco Bissolotti and Wanna Zambelli, published in 1985 by Aclap of Cremona (Production Coordinator, Franco Feroldi) and presented in December of the same year at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. Photo: © Claudio Mazzolari, Cremona

130 years since his birth. The story of Simone Fernando Sacconi, one of the greatest violinmakers of the twentieth century

More than a century after his birth, former student Wanna Zambelli invites us to rediscover the story of a man who championed artisan creativity, grounded in patience, deliberation, and sensitivity.

by Ludovica Palmieri

Artribune

Rome, May 23, 2025

May 30, 2025 marks the 130th anniversary of the birth of Simone Fernando Sacconi (Rome, 1895 – New York, 1973), the Italian-American master luthier and one of the 20th century's foremost experts in this timeless art. Today, his former student Wanna Zambelli remembers him fondly in this "narrated" interview, recognising not only his remarkable ability to convey even the most complex knowledge with simplicity and clarity, but also his consistently warm, affectionate, and human approach to everyone he encountered, regardless of their status.

Simone Fernando Sacconi, as remembered by former student Wanna Zambelli

After a disheartening year at a technical school, unsure of what to do next, I sought advice from a painter in my hometown of Volongo, near Cremona, who directed me to the Violin Making School (Scuola Internazionale di Liuteria). And it was in the Palazzo dell'Arte – now home to the Violin Museum, but then the school building – that I met the Italian-American luthier and restorer Simone Fernando Sacconi in 1968, during my first year of study, on one of his rare visits and extraordinary lessons.

The luthier Simone Fernando Sacconi and his illustrious acquaintances

I remember him surrounded by students – there were only about ten of us – all curious and intensely focused on his explanations. Well before his arrival, the anticipation had been palpable: his visit was considered a major event. I wondered who this renowned expert from America was – the man famed for having repaired over three hundred antique instruments and worked with exceptional musicians such as Casals, Kreisler, Enescu, Heifetz, Elman, Cassadó, Huberman, Flesch, Busch, Francescatti, Feuermann, Milstein, Piatigorsky, Zimbalist, Salmond, Fournier, Szigeti, Stern, Menuhin, Oistrakh, Ricci, Szeryng, Rostropovich, Primrose, Rose, Perlman, Accardo, Ughi, Zukerman, and Du Pré. It was said that he had even had personal relationships with Toscanini and many of the era's leading composers – Strauss, Debussy, Zandonai, Respighi, Casella, Mascagni, and Pizzetti.

I longed to speak with him, but as I was just starting out, I didn't have the courage. Then in 1971, during another visit, I had the chance to talk with him. I remember him walking past the workbenches, stopping at mine, and carefully examining the cello I was building. He gave me valuable advice with genuine interest.

Fernando Sacconi at master luthier Bissolotti's workshop in Cremona

Later, I met him again at the workshop of master luthier Francesco Bissolotti, where I continued my training after school. It was between the summer and autumn of 1972 that I had the opportunity to get to know Sacconi better. His passion for violin making was infectious and, even after more than fifty years, remains one of the driving forces in my life.

At the workbench nearly every day, he was busy building a violin based on the 1715 Stradivari Cremonese model, working alongside Bissolotti and constantly surrounded by people seeking explanations and guidance. During this period, he was finalising his book The "Secrets" of Stradivari, with assistants frequently visiting him to discuss the manuscript. However, he was so busy that, after a while, he began arriving at the workshop ahead of schedule to work in peace – early in the afternoon, when I was the only one there, as I stayed through lunch because I lived outside Cremona.

Those were unforgettable moments, filled with precious lessons. I spoke to him naturally, without fear, knowing he would understand exactly what I meant – even if my questions were vague. And he, even though I was the newest student, spoke to me as if I were a peer or a famous violinist. He explained things so clearly and simply that they seemed obvious. He was not only a great luthier, but a great teacher and a great man.

Simone Fernando Sacconi: a tireless experimenter

Alongside tool-making in Bissolotti's workshop, and with his help, Sacconi had begun the preparation of a new varnish that he wanted to resemble that of Stradivari. He later described the preparation process in meticulous detail in his book. Always in pursuit of rare natural substances and elusive resins, he was constantly experimenting.

He even spoke to me about violin making while I drove him in my tiny Fiat 500 to visit his wife Teresita, who was hospitalised in Cremona. I fondly remember his initial hesitation, as if unsure about getting into such a small and fragile car – but then, out of necessity, he took courage, and he never once complained about the driver.

Simone Fernando Sacconi's love for antique instruments

I was captivated by his deep love for antique instruments. He loved them more than anything else; when he took them in his hand, it was as if he was caressing them, handling them at the same time with a certain strength. He talked about the instruments by name, as if they were people, and he remembered all the details – he had an incredible memory. He said he would have liked to write a book on restoration, to explain all his techniques perfected over the years at Herrmann and Wurlitzer (great restoration houses in New York); unfortunately, he did not have the time.

The importance of Simone Fernando Sacconi's teachings

Over the years, I've come to appreciate the importance of Sacconi's teachings. I've realised that his method – rooted in a specific mental approach, even before the technical aspect, and in demanding the highest standards, following the tradition of the old masters and respecting the natural rhythm of artisan work – is the key to achieving quality results. There must be joy in creating an instrument: working solely for financial gain, or even mass-producing them, does a disservice to the craft.

Simone Fernando Sacconi and the celebration of artisan creativity

Simone Fernando Sacconi brought the value of artisan creativity back to the forefront of modern industrial society – a creativity shaped by patience and meticulous care. He brought passion and the desire to do things well back to the forefront. That, to me, is the legacy he left behind, and the one I have tried to pass on to my many students during my 44 years of teaching at the Cremona Violin Making School, with the hope of having planted a fruitful seed.

Some say that in a few years, artificial intelligence will be able to produce "perfect" violins, eliminating the need for luthiers, their sensitivity, creativity, and knowledge – their ability to feel and understand wood, which varies so much by origin, seasoning, and countless other variables. But what I learned from Simone Fernando Sacconi is this: true violin making can only come from human hands. Because real Instruments – with a capital "I" – whether violin, viola, cello, or double bass, can only be born and truly sing when crafted by a human being.